Fanny Bixby Spencer: Pioneering Painter

|

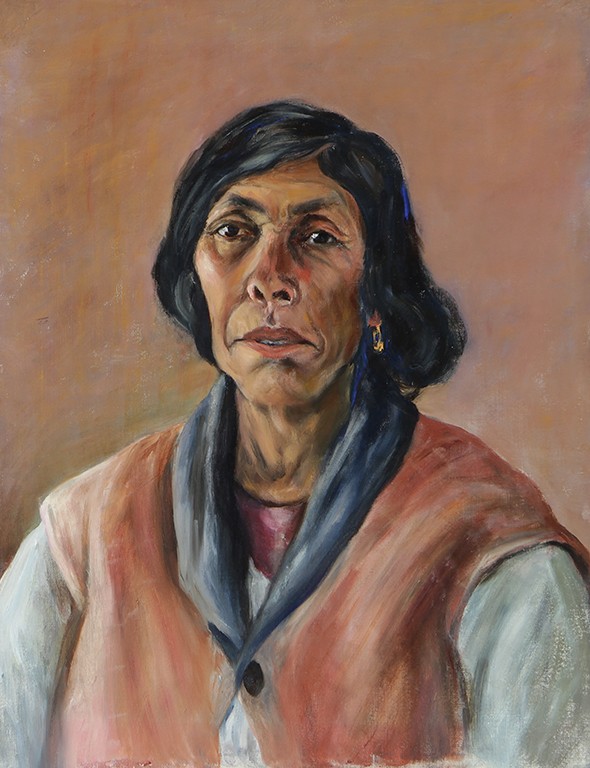

| Fanny Bixby Spencer, c. 1915 |

Women’s History Month

March is Women’s History Month, an opportunity to celebrate the great women who have shaped the course of history and contemporary society. Here we focus on Fanny Bixby Spencer, a Southern California heiress who used her family’s wealth and status to aid victims of abuse and prejudice. As both a hobby and a means to process the injustices she witnessed, Spencer painted continuously throughout her life. In this post we look briefly at the many impressive exploits of Spencer in her short years on this world and discuss her painting of María Tomé.

All The Money In the World

Born on November 6, 1879 in Rancho Los Cerritos, Fanny Bixby Spencer was the youngest daughter of Jotham and Margaret Hathaway Bixby. Her family was fabulously wealthy. Jotham was the president of the Bixby Land Company, the Palos Verdes Company, the Jotham Bixby Company, the Chino Valley Cattle Company of Arizona, and the National Bank of Long Beach, as well as being involved in a great many more local companies and organizations. He was not only wealthy, but powerful, a status that earned him the title, "the father of Long Beach.” Unfortunately, all the money in the world could not save Fanny Bixby’s three older sisters from dying in their childhood, leaving her as the sole heir to the vast fortune. Her education began at the prestigious Marlborough School in Los Angeles, the Pomona Preparatory School, and was further continued at Wellesley College. In her higher education, she believed that the most valuable aspect of her studies was art. During this time, she became familiar with the use of charcoal and pastel, most enthusiastically depicting vases with fruits and flowers. She would continue to paint and draw throughout her life, but most of her work was gifted to friends and family.

|

| Fanny Bixby Spencer as a Special Officer in the Long Beach Police Department, c. 1910 |

A Born Fighter…

With a strong family background in abolitionism and women's suffrage, Spencer discovered her own interest in political justice and humanitarian work while traveling the world at the age of nineteen. She spent a great deal of time in Italy and later Boston helping those less fortunate than her before ultimately returning to her home state of California. Refusing to settle into the socialite’s life, in 1908, she successfully made the case to the Long Beach Police Department that they needed a female officer on staff to deal with cases pertaining to women and children. She was instated as a deputy constable—one of the very first women in the United States to wear the badge. Over the next seven years working there she was called upon to assist in the aftermath of suicide attempts, domestic abuse, and children who had recently lost their parents. All the while she suffered the ire of those that felt it untoward for a woman to be in that line of work. The stress of her position weighed heavily on Spencer, who found catharsis in poetry and in her art. During the course of fulfilling her police duties, Spencer expressed her enthusiasm for art by sponsoring an art show which featured over 200 works. Spencer was forced to discontinue her work as a police officer after becoming seriously ill.

|

| Fanny Bixby Spencer, 1915 John Hubbard Rich (American, 1876-1954); California Oil on canvas |

And Pacifist

Bixby’s exploits are too lengthy even to summarize, but it should be noted that in addition to all else, she was a life-long political activist. As the president of the Political Equality League in Long Beach, she fought for women to get the right to vote. Upon earning this right, Spencer registered under the Socialist Party and served as the secretary of the Long Beach branch. With the beginning of World War I, Spencer began her participation in anti-war groups, disagreeing with America's possible involvement in the war. Regardless of her social and financial status, Spencer was increasingly ostracized by others over time due to her political radicalism. She is still remembered to this day for donating land, money, and time to helping immigrant families and those down on their luck to get access to housing and education for their children. In 1918, Fanny Bixby married the dock worker, Carl Spencer, whom she had met at a union meeting. The pair adopted and raised over a dozen children and paid college tuition for many others who were not able.

|

| María Tomé, 1929 Fanny Bixby Spencer (American, 1879-1930); Orange County, California Oil on pulp board 1627 Gift of Carl Spencer |

Tomé

Spencer died at the age of 50, on March 31, 1930. Most of her wealth was donated to charities and families in need with only a small amount going back to her family. Five years later, her husband, Carl, gave three of her paintings to the not-yet-opened Bowers Museum for inclusion in their displays. The three works were of local Mexican- and Native-American sitters: Señor Ramón Montejano from Delhi, Señorita Guadalupe Hidalgo, and Señora María Tomé of Costa Mesa. Two of these paintings were deaccessioned by the Bowers over the years, but the portrait of Tomé, an Apache woman who lived with her husband on a ranch in modern-day Costa Mesa, remains to this day in the Bowers’ Fine Art collection. According to a descendant of Tomé, she had originally not been interested in sitting for the portrait until she was offered $200 to do so, about $3,500 accounting for inflation. That María Tomé did sit for the painting has become a source of pride for her family who have come to visit the museum and see the painting ever since it was first put on display.

|

| Descendants of María Tomé at the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana on Friday, December 16, 2016. (Photo by Ed Crisostomo, Orange County Register/SCNG) |

A Rich Style

This painting of María Tomé appears to be consistent with Spencer’s style in her later years, as evidenced by similar works in the collections of the Rancho Los Cerritos Historic Site. It is an oil painting on a laminated wood pulp board. The paint appears to have been applied with a direct wet on wet technique which is notably similar to that of the Orange County artist, John Hubbard Rich, the very same artist who painted Spencer’s portrait in 1915. Though damage over the years led to some chipping of the paint, Spencer made the conscious decision to leave some of the ground visible.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments