Ancient Chinese Bronze Wine Vessels in World of the Terracotta Warriors

|

| Collage of wine vessels superimposed over one of the tripod vessels (ding) discovered at the Yangjiacun site |

Ritual bronze wine vessels are among the most exceptional objects discovered within the tombs of China’s pre-imperial dynasties. For the ancient Chinese, life continued after death and this central and enduring belief compelled aristocrats to bring their most important earthly possessions with them, so that they could live properly in the afterlife. Among these objects, aristocrats buried with them impressive cast bronze vessels used for serving food and wine in ceremonial banquets. The consumption of wine was very much institutionalized and was a crucial process within the complex socio-ceremonial fabric of ancient China. The number of vessels required was determined by the nature of the ceremony, and the wealth and status of an individual were displayed not only through the use of precious material, or by fine craftsmanship, but also through the ritual consumption of abundant food and drink, requiring potentially many vessels at one time.

Though bronze wine vessels vary in style and in execution over the roughly two thousand years that archaeological evidence indicates continuity in the use of such objects, they are curiously each used in a similar ritual to serve wine. This Bowers Blog examines some of the many bronze wine vessels featured in World of the Terracotta Warriors: New Archaeological Discoveries in Shaanxi in the 21st Century that have profoundly transformed our understanding of the formation of ancient China.

|

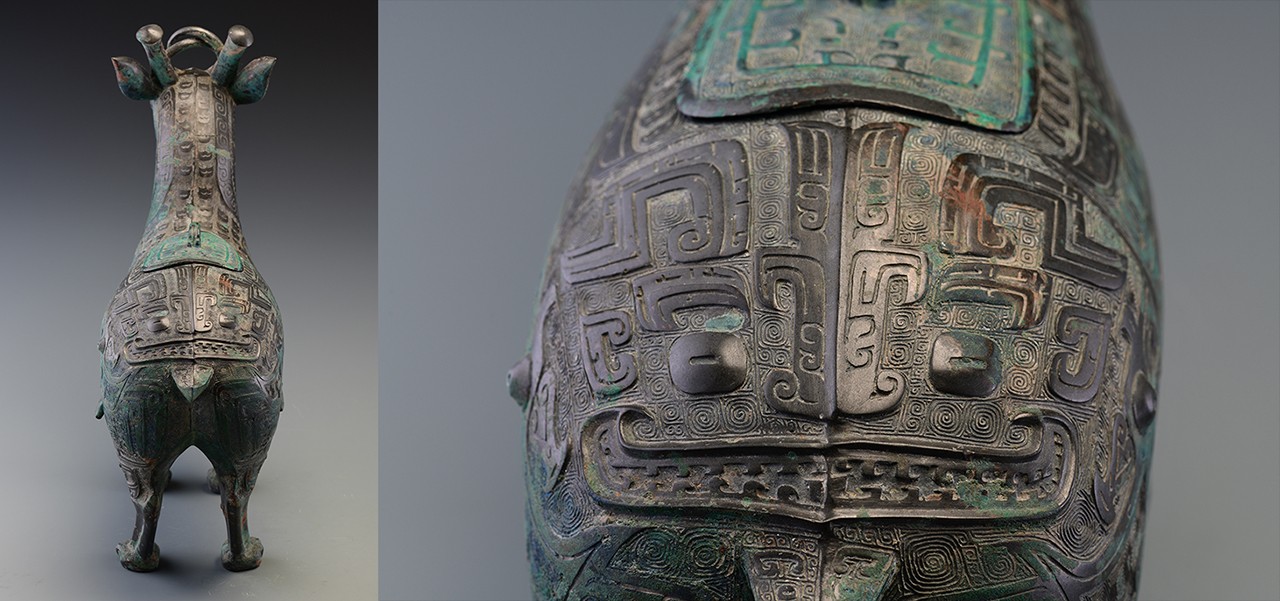

| Animal-Shaped Wine Vessel (Zun) Early Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1046-1000 BCE) Bronze; H: 12 5/8 in. Excavated from Shigushan Site, Baoji in 2013 Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, SKGC001647 (M4:214) |

As the homeland of the Western Zhou dynasty, Shaanxi served as the political and cultural center of China from c. 1046 to 771 BCE. Newly unearthed bronzes from tombs in the area not only marked technological breakthroughs, but also recorded changes over time to rituals and to the hierarchical political system of Zhou society.

Two unique animal-shaped bronze wine vessels, known as zun, were excavated in 2013 from the Shigushan site, one of which was this complex and mysterious wine vessel in the form of a chimeric animal. The main body takes the form of a deer and is incised with relief and in negative line cloud and thunder patterns. It stands sturdily on four predatory paws and has the face of a rabbit, large round eyes, a short tail, the antlers of a deer, tall, cupped ears, and fish fins on each side of its belly. Though some of the animal aspects have parallels within the western Zhou bestiary, the specific combination embodied in this zun on display is unique. Viewed from behind, the pattern culminates on the back in the expression of an even more mysterious deity.

|

|

| Two views from behind of mysterious deity relief, SKGC001647 (M4:214) |

Animal-shaped zun such as this vessel are rare among bronze wine vessels and can be viewed both in terms of the animals it resembles and in terms of the standard vessel types. In some cases, the animal aspect of the piece eclipses the function; while in others, the ritual function predominates. Ultimately, many facets of animal-shaped zun remain a mystery.

|

| Vessel (Hu) Spring and Autumn period (770-475 BCE) Bronze; H: 20 7/8 in. x D: 9 1/4 in. Excavated from Liangdaicun in 2006 Rui State Site Museum, 273 |

Bronze wine vessels, known as hu, were used in banquet ceremonies from the Warring States period (c. 475 BCE) to the Western Han period (c. 206 BCE). This large hu was excavated from Liangdai Village Site in 2006 and inscriptions inside the lid indicate it was commissioned by Zhong Jiang, a powerful consort to the Duke of Rui. The main body is decorated with incised relief of sinuous and coiled double dragons patterns, which contrasts with the barer neck and lid incised with horizontal bands of ring patterns. Perhaps the most fascinating characteristic of this vessel are the mysterious handles flanking it—designed to look like trunks, but terminating in draconic faces. The excavations at the Liangdaicun and Liujiawa sites have transformed our knowledge of this “lost” State of Rui, which was enfeoffed at the beginning of the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1046 BCE), and lasted about 400 years before it was eventually annexed by Duke Mu of the Qin State in 640 BCE.

|

| Vessel (Hu) 錯金銀提樑壺 Spring and Autumn period (770-475 BCE) Bronze with gold and silver inlay; H: 8 1/2 in. x D: 4 in. Excavated from Shiyangmiao in 1973 Chencang District Museum, 15 |

Unearthed in 1973 from Shiyangmiao temple, this hu is one of the most remarkable of its kind to have ever been discovered. This hu is heavily inlayed in gold and in silver with geometric patterns and with interlacing, coiled dragon and phoenix patterns. It features a simple, round lid and rings on the sides, which a dragon head-shaped chain handle has been attached to—a style that was adopted by later generations. Multiple inlay marks indicate inlaid turquoise, which has all but fallen off. This particular vessel is an important precedent indicating the sophistication of inlay technique much prior to the techniques of the subsequent western Han period (206 BCE – 9 AD). Taken together, if this blog has taught us anything, it is that the ancient Chinese certainly knew how to drink wine in style both in the present and in the afterlife.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Images provided by the Shaanxi Cultural Heritage Promotion Center

This exhibition is jointly organized by the Shaanxi Provincial Cultural Heritage Administration, Shaanxi Cultural Heritage Promotion Center, and Emperor Qin Shi Huang's Mausoleum Site Museum of the People's Republic of China, and Bowers Museum in the United States.

Comments