2002 North Main Street

Santa Ana, California 92706

TEL: 714.567.3600

Silk and Gold: Chinese Embroidery at the Bowers

|

| Embroidered Panel, late 20th Century Miao culture; probably Guizhou Province, China Silk and metallic thread on possibly silk backing; 14 × 31 1/2 in 2017.3.7 Gift of Anne and Long Shung Shih |

National Embroidery Month

February is National Embroidery Month in the United States, a timely celebration given the significance of embroidery in the Bowers Museum’s current special exhibition, Guo Pei: Art of Couture. As a Chinese couturiere, Guo Pei draws on the long tradition of Chinese embroidery, often pairing intricately embroidered fabrics with silhouettes and forms that are her unique fusions of cultural traditions from around the world. Both in the exhibition and throughout the history of China a great many different styles of embroidery have been pioneered and employed. This post looks at a small selection of Chinese embroidery in the Bowers’ collections, highlighting similar styles of pieces to those that inspired Guo Pei and her embroidery technicians.

First Stitch

Chinese embroidery dates back into neolithic times. Silk embroidery, by far the most pervasive and best-known medium for Chinese embroidery work became more common around the time that the silkworm was first domesticated around 5,000 years ago. There are a great many different styles of Chinese embroidery which have become associated with different periods in history and with China’s various regions. The four most famous styles of Han Chinese embroidery are Su, Xiang, Yue, and Shu, respectively coming from the Suzhou, Hunan, Guangdong, and Sichuan Provinces. They vary in the types of stitch and techniques which they employ, and in their overall approach to capturing their subject in a painterly or more abstract way.

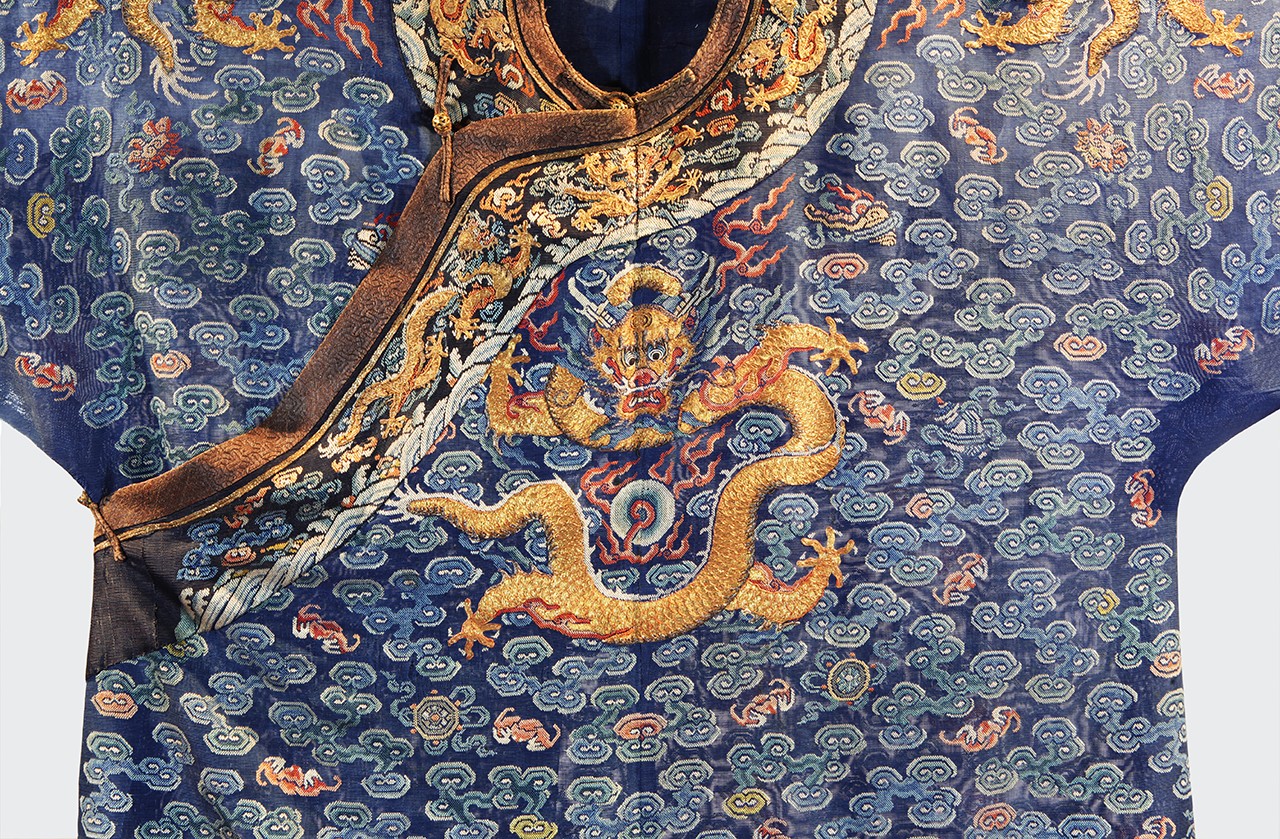

| Man’s Semi-Formal Court Robe (Jifu), Late Qing dynasty (1870-1911) China Gold, gauze and silk; 54 × 86 in. 83.13.1 Gift of Mrs. Herbert Wilson |

Sew-phisticated Robes

The most intricate historic examples of Chinese embroidery in the Bowers collections tend to be found on upper body wear like robes and jackets. This intricately designed robe is from the late Qing dynasty (early 20th century). During this period, a dress code was strictly enforced at the imperial court and robes replete with symbolism were standardized for everyone from the imperial family to the general population to signify rank and social standing. The dragon motif, seen throughout the body of this robe, is a symbol of the emperor who granted members of the court—those outside of the imperial family—the privilege to wear a robe depicting a dragon. Color also signifies the rank of an individual and the blue color of this robe helps to identify it as one worn by a court official. The symbols embroidered into the robe are typical Chinese emblems of power, wealth and harmony. The central figure is the dragon, a well-known symbol of the natural world, adaptability and transformation. This robe is constructed of an open-weave raw blue silk with gold metallic thread and other thread used in numerous embellishments. Unlike traditional European garments of royal lineage, the gold thread is not embroidered directly onto the silk material. The thin metallic thread is couched, a technique where pairs of threads are gathered and held by a thread of contrasting color using many small perpendicular stitches. This creates long lines with a huge variety of motions.

| Shoe for a Bound Foot, c. 1875 China Silk, paper, braid and cloth; 6 1/4 x 1 7/8 x 5 1/4 in. 38045.12 Gift of Miss Grace M. Rowley |

Rank Insignia (Buzi), 1890-1910 China Silk and gold-wrapped thread; 12 1/4 x 12 in. 2007.1.46 From the collection of Fyle Edberg and Paul Foote. Gift of Helen Jahnke |

Embroidered Fan with Carved Handle, Qing Dynasty (1800-1876) Han people; China Ivory and embroidered fabric; 11 1/4 x 17 3/8 in. 95.34.1 Gift of Mrs. Aurel Schwarz |

Intermittent Flossing

Anything made of fabric can be embroidered. During the Qing dynasty, the aesthetic sensibilities of the imperial court led to embroidery work appearing on every element of clothing from head to toe, on daily use accessories, and even on patches marking one’s rank. Looking closely at the above objects we can see a variety of different embroidery techniques employed. Satin stitch, a staple of Chinese embroidery, is a straight stitch tightly packed together in parallel to give the embroidery work the satiny sheen that gives it its name. We can see it used on this women’s shoe to create floral elements from monochromatic blocks. On this same piece, couched orange and white silk thread is used to shape designs from thicker, silver threads sitting on the surface of the fabric. A variant of satin stitch called shaded (or long and short) satin stitch is employed on the embroidered fan (kossu). Here we can see that rather than monochromatic blocks, the colors used for leaves, petals, and bird feathers create dynamic gradients. Aptly named stem stitches are used to create petioles and other floral elements. In the rank badge (buzi), large patches which were adhered to the fronts and backs of court robes to indicate rank, a tightly packed knotted stitch is used to create the silver pheasant characteristic of the fifth rank of late Qing dynasty civil officials.

| Festival Jacket, mid to late 20th Century Miao culture; Guizhou Province, China Cotton, silk, feathers and Job’s tears; 64 × 50 in. 2015.9.20 Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Long Shung and Anne Shih |

Daoist Priest’s Robe, 20th Century Yao culture; probably Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China Cotton and silk; 44 1/4 × 34 1/2 in. 2016.13.28 Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Long Shung and Anne Shih |

Butterflies and Dragons

Embroidery is every bit as characteristic of the clothing and textiles of the minority cultures of China with a vast range of different styles and techniques employed regionally. Here we look at just two examples from the Miao and Yao cultures of Southern China. The feathered garment above was originally worn by Miao village leaders during the Guzang festival, a celebration of a legendary couple’s lengthy courtship which takes place every 12 years in Guizhou Province. Over time it has become a part of the Miao culture’s regular festival wear. The appliqued silk felt panels are heavily embroidered with butterfly motifs in a satin stitch reminiscent of what is used by Han Chinese embroiderers. Daoist priest robes made by the Yao culture of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region also use silk embroidery floss, but to a vastly different effect, alternating a satin stitch for filling and individual straight stitches for more detailed elements like halos and characters.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments