2002 North Main Street

Santa Ana, California 92706

TEL: 714.567.3600

Hawaiian Lei Niho Palaoa

|

| Necklace (Lei Niho Palaoa), early 19th Century Hawaiian culture; Hawaii, United States, Polynesia Hair, fiber and walrus ivory; 11 1/4 x 7 7/8 x 2 1/2 in. 2018.5.1 Bowers Museum Purchase Photograph courtesy of Bonhams |

A New Acquisition

When it comes to Hawaiian necklaces, the subject can be a somewhat hairy one, though perhaps not for the reasons one might expect. In this post we examine the Bowers Museum’s recently acquired lei niho palaoa—a Hawaiian necklace which in terms of importance stood second only to their brilliantly colorful feather work cloaks (‘ahu‘ula) and headdresses (mahiole). Several details set this necklace apart from what we might expect, though, so we also look at what the necklace’s unique medium and design can tell us.

|

| Detail of 2018.5.1 Photograph courtesy of Bonhams |

The Tooth of the Matter

As vacationers to the Aloha State might know, lei is the Hawaiian word for necklace. The other two words of the commonly used vernacular name, niho and palaoa, collectively mean sperm whale tooth. These describe the material from which the necklace’s hook-shaped pendant is carved, but this name is somewhat misleading. Following last week’s post, Captain James Cook sails into relevancy once more by having collected some of the first examples of lei niho palaoa. Already by his 1778 discovery of Hawaii, many of the pendants were made from substitutes such as shell, pig teeth, or coral. This can be explained in part by the limited supply of whale teeth. Whales were revered in the polytheistic Hawaiian religion as incarnations if the ocean god Kanaloa. The world’s largest mammal was never hunted by Hawaiians, but instead the teeth were collected from beached whales.

|

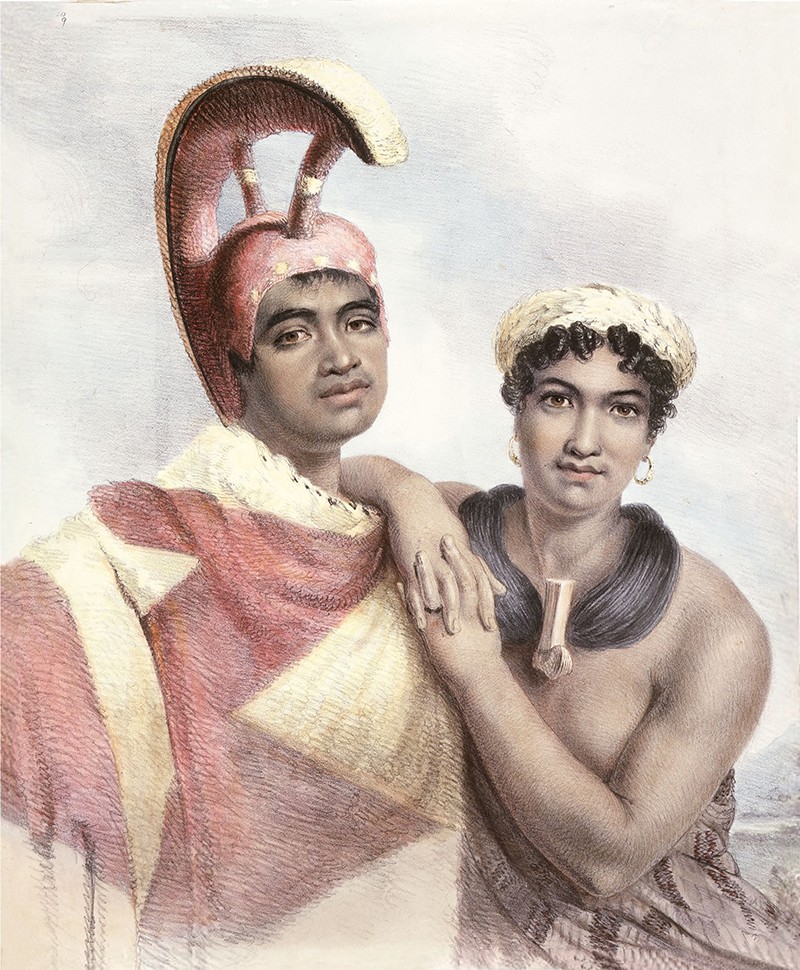

| Boki, Govenor of Oahu, and his wife Liliha wearing a lei niho palaoa after a painting by John Hayter, 1824 |

Lei to Win

For whale teeth, rarity and societal importance of the medium went hand-in-hand. Shores on which whales regularly beached were well-guarded by chiefs and priests, and the ownership of their bodies was codified in this saying:

The accuracy of this statement can be confirmed by the material culture of the islands. Objects which included sperm whale parts were almost exclusively reserved for wear by the chiefly class and lei niho palaoa—which were worn by both male and female aristocrats on ceremonial occasions and during battles —were no exception. In the 19th Century when European artists began depicting Hawaiian aristocracy in paintings and drawings, many chose to be memorialized wearing their lei niho palaoa, along with their ‘ahu‘ula and mahiole; all essential pieces of royal dress.

|

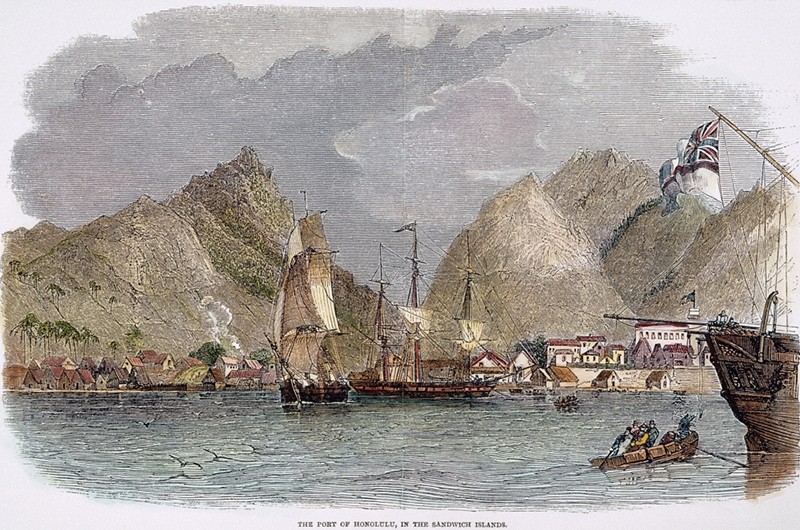

| The Port of Honolulu, 1849 |

The Tusk Trade

Considering all the elevated status of whale, why is it then that this lei niho palaoa is not made from the animal’s teeth? More curiously still, how is it that this necklace has been confirmed by analysis to have been made from the tusk of a walrus, a creature whose southernmost range lies thousands and thousands of miles to the north of Hawaii? Cook’s discovery of the Sandwich Islands, as Hawaii was then known, was the start of their role as a pivotal rest spot in the middle of the Pacific. In the early years of the 1800s, American and European whalers began coming to the Sandwich Islands and trading excess from their hauls for the types of things a sailor cannot get out on the open ocean. Walrus tusk was one of these materials which was traded, and it became a common material for lei niho palaoa as it was difficult to distinguish from whale teeth.

To Put on Hairs

Various theories have been proposed regarding the significance of the pendant including that it was a ceremonial fishhook seen on some Polynesian Islands or an abstraction of a human head with an extended tongue, but the likeliest option is that the pendant served as a vessel for one’s mana or spiritual energy. Though it was likely the shape of the pendant and little else which was important to Hawaiian chiefs, the band of the necklace is every bit as interesting as the pendant. It is composed from human hair. As with many cultures, hair was an important repository of one’s power. Cutting off one’s hair so that it could be braided into some 1700 feet of continuous braid required for an average lei niho palaoa would have been an immense sacrifice. These hair bundles were generally bound in one or two places with fiber cord to maintain the general form of the pendant. This necklace is an extremely unique example in that it is bound in a total of twenty places. This could be representative of a specific genealogical lineage or the result of repair work done sometime during the 19th Century.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments