2002 North Main Street

Santa Ana, California 92706

TEL: 714.567.3600

Knowing Korwar: Ancestor Figures from Cenderawasih Bay

|

| Ancestor Figures (Korwar), 19th Century Cenderawasih (Geelvink) Bay, West Papua Province, Indonesia, Melanesia Wood and mother-of-pearl F79.67.1, 85.24.1 Gifts of Mr. and Mrs. Edwin R. Gamson and Dwight V. Strong |

Remembrance

The way in which forebears are remembered differs all around the world. In most western cultures, the dead are buried or cremated and memorialized with tombstones, grave markers, or funerary urns. For the cultures living around New Guinea’s Cenderawasih Bay, the dead and the spiritual power that they could invoke were captured in small, wooden ancestor figures called korwar, a term that—at least according to some sources—translates to “spirit of the dead.” This post looks at the history, production, use, and design of two korwar in the Bowers Museum’s Spirits and Headhunters: Art of the Pacific Islands exhibition.

|

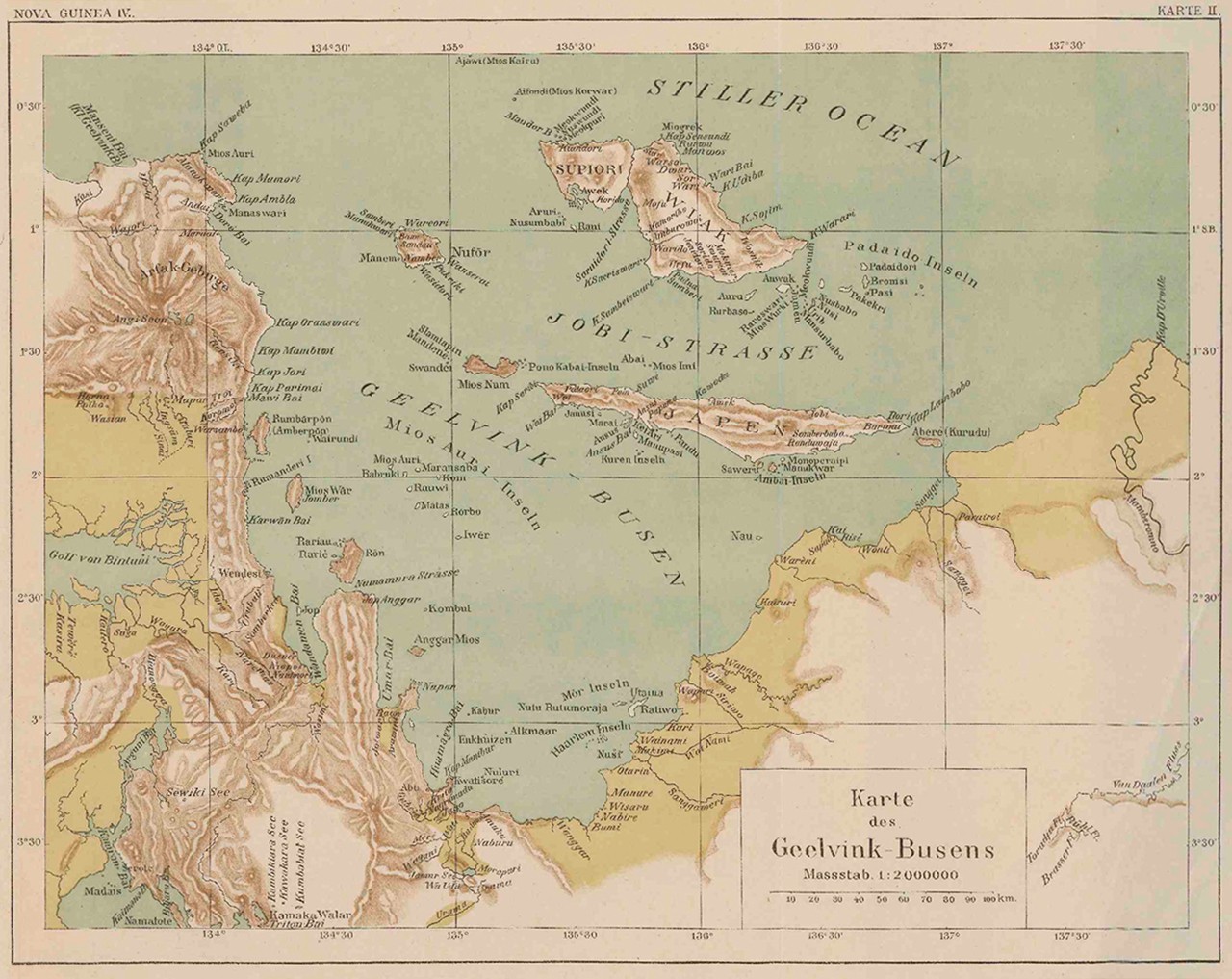

| Map of Cenderawasih (Geelvink) Bay c. 1900 |

The Indonesian Connection

As noted in another post on the glass earrings from Cenderawasih Bay, the northwest coast of New Guinea has had a history of trade with island Indonesia for at least the past 5,000 years. Unfortunately, the development and evolution of korwar is almost entirely unknown, shrouded by a lack of written records but also by the susceptibility of the medium to decay given the environmental conditions of the region, the occasional destruction of korwar by those that consulted them when they failed to perform as intended, and the far more egregious large-scale destruction of ancestor figures by Dutch missionaries following their arrival in New Guinea in 1855. At least one korwar in the collections of the De Young Museum has a 95% probability of dating to around the 14th century; it likely survived as long as it did due to having been stored in a cave. This figure in particular bears a likeness to woodcarvings from Indonesia, possibly indicating that the style of carving was developed elsewhere and regionally adapted.

|

| Ancestor Figure (Korwar), 19th Century Cenderawasih (Geelvink) Bay, West Papua Province, Indonesia, Melanesia Wood; 6 1/2 in. 85.24.1 Gift of Dwight V. Strong |

Body Double

Due to their outlaw by the Dutch as pagan ritual items, korwar are no longer made. Accounts of how they were made are relatively limited as no anthropologists were witness their creation, but many principals of Papuan ritual objects apply here. Korwar were sculpted by specialists who were both masters of carving and religious experts. In secret these men traveled into the bush to find the perfect tree from which to create their figure; according to some sources going to painstaking lengths to draw the spirit of the dead into their carving. The criteria for being immortalized were equally selective. Those considered for the honor were usually important to a village such as a family or clan head, or leader of an expedition. Those who died suddenly or prematurely were also sometimes remade as korwar due to the belief that they might haunt their family if they were too quickly forgotten. The sculptures were made from lightweight wood and in varying sizes from handheld figures to about two feet in height so as to be easily transportable.

|

| Ancestor Figure (Korwar), 19th Century Cenderawasih (Geelvink) Bay, West Papua Province, Indonesia, Melanesia Wood and mother-of-pearl; 14 1/2 × 4 3/4 in. F79.67.1 Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edwin R. Gamson |

Fair Weather Figures

The korwar image played an active part in both the spiritual and visual expressions of daily life. Figures like the ones featured in this post were typically placed in the family home where they functioned as an active presence in both the family and community. Korwar were consulted for significant life events such as births, marriages, and deaths. It was believed they could heal the sick and ensure fertility in women. They were also summoned for important communal ventures such as voyages across the bay. In this latter case, the korwar was beseeched for favorable winds and no rain. In addition, on headhunting expeditions, the warriors would wear male korwar amulets into battle. These amulets were thought to provide protection by blinding the enemy and rendering its own people invisible. Korwar figures were also feared by cultures that did not make them as it was widely held in the area that they could make someone ill or even kill them.

|

| Korwar featuring human skulls in the collections of the Louvre and Museum Nasional Indonesia |

Mini Miniature

Even today korwar are the defining art form from northwest New Guinea—in general woodcarvings from the region are often described as “korwar style.” As a subgenre of ancestor figures, korwar are identified by a few near-ubiquitous characteristics: their distinctive anchor- or arrow-like noses; an oversized head in relation to its body, one which tends to be flat on its underside; either a seated position or the standing position seen in both of the Bowers’ examples; they hold shields, fences, or smaller anthropomorphic figures which are incised with elegant openwork; and they sit on rounded bases. Older examples sometimes replaced the head of the sculptures with or hollowed them out for the skull of the deceased as evidenced by korwar in the collections of the Louvre and Museum Nasional Indonesia. Depending on how the different styles of korwar are grouped there are three or five distinct regions of production; going by the latter framework, four of these groups are along the coast and islands of Cenderawasih Bay and the fifth is found on a small archipelago west of New Guinea.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments