2002 North Main Street

Santa Ana, California 92706

TEL: 714.567.3600

That’s Got to Sting: Barbed Blades from the Admiralty Islands

|

| Dagger, 19th Century Admiralty Islands, Bismarck Archipelago, Manus Province, Papua New Guinea, Melanesia Wood, stingray barb, fiber and beads 2019.20.2 Bowers Museum Purchase |

Blade with a Barb

The Bowers Blog has previously spent a lot of time focusing on the art of Admiralty Islands, a small chain located in Papua New Guinea’s Bismarck Archipelago. In terms of material culture, the islands were historically notable for their blades made from obsidian—previously mentioned in Dragon Glass: Taking Stock at the Bowers Museum—and for the gargantuan handle-adorned feast bowls discussed in Grand Admiralty Island Feast Bowl. Today’s post looks at a new acquisition to the Bowers Museum’s collections: An Admiralty Islands knife with a stingray barb blade.

|

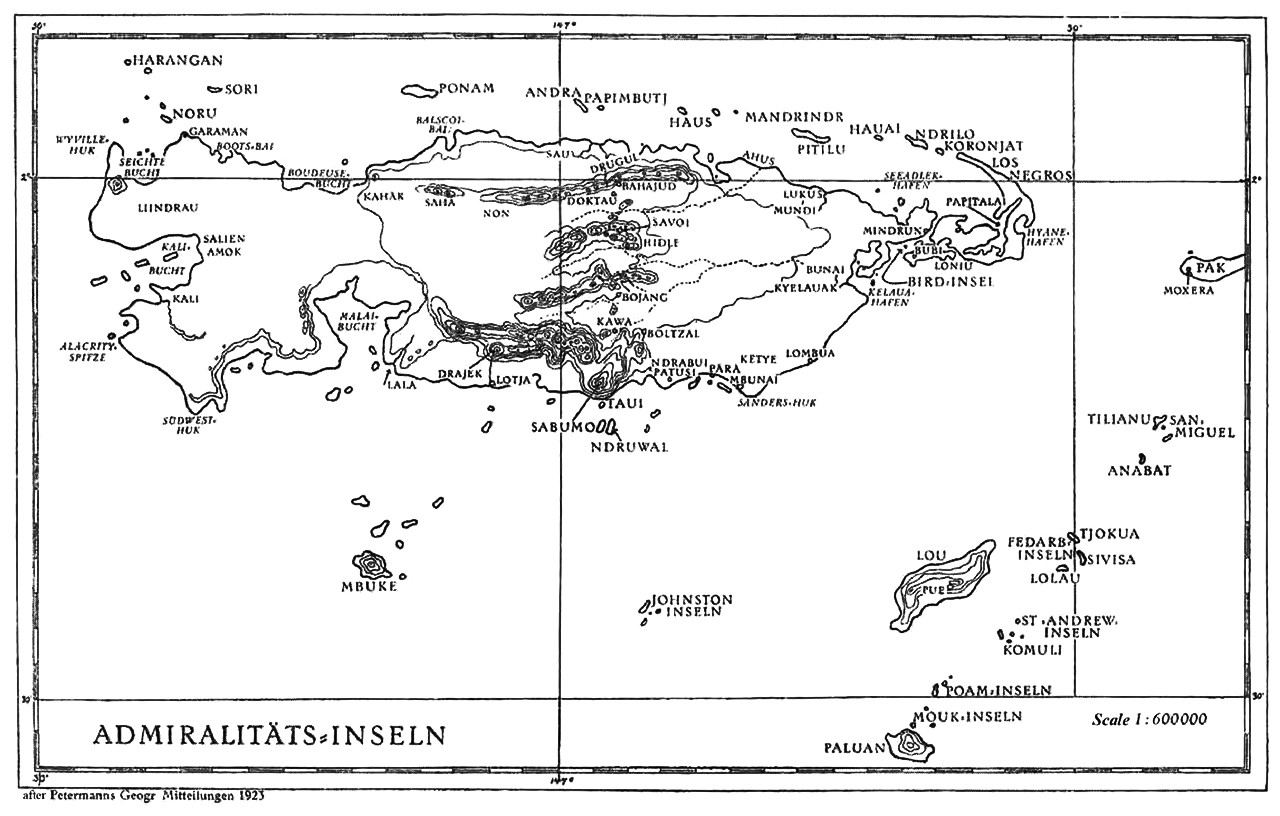

| Map of the Admiralty Islands featured in Hans Nevermann's Admiralty Islands (1934) |

Stands to Resin

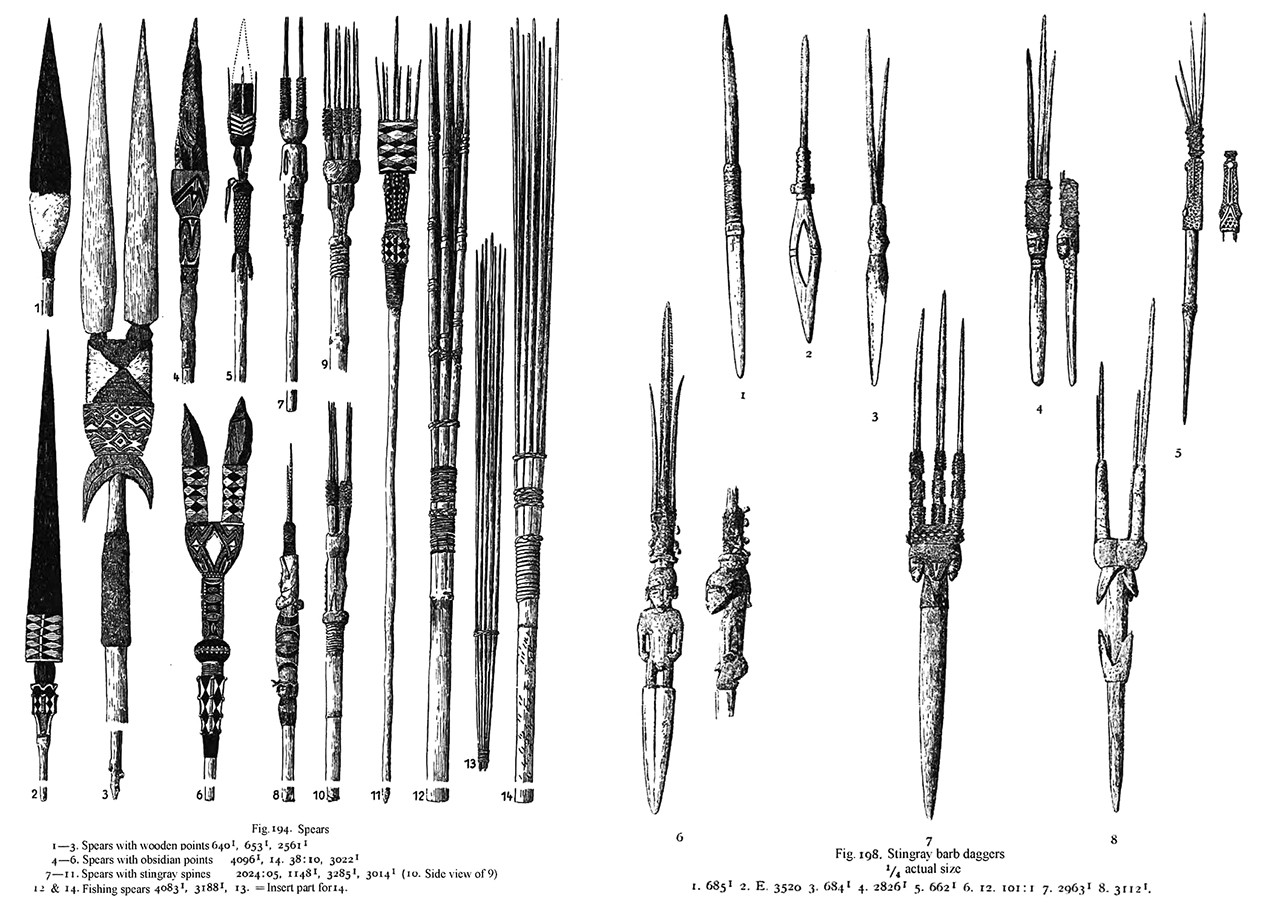

Spears and daggers were the two principal types of weapons used on the Admiralty Islands, with most combat consisting primarily of fighting with thrown or hand-wielded spears. Just as was the case with obsidian spears, the construction of stingray barb spears began with the blade or blades—upwards of eight smaller barbs could be used—which were surrounded with parinarium nut resin and then socketed into a splint made from wood and often further decorated with carvings, a wrap, glass beads or so on. It would have been up to the wielder rather than the maker of the tip to create the shaft for the spear, and these spear points were designed so that they could easily be socketed into shafts. The usage of stingray daggers in warfare has been treated with some skepticism by ethnographers, but evidence seems to confirm their usage. They were used in the later stages of a battle, where warriors could finish off wounded enemies by targeting vulnerable locations. Daggers were created in a similar way to spears, though their midsections tended to have a distinct appearance to that of the spear tip and there would have been no unadorned bottom section that could be socketed into a shaft.

| Photographs of stingrays taken off the coast of the Admiralty Islands by Peter Keller and Ed Roski on their 2006 expedition to the islands |

Everybody Loves Ray

Open ocean fishing was carried out by the coastal-dwelling Manus and Makantol peoples of the Admiralty Islands. They employed a variety of different methods to catch fish including traps and lures, but the same baited hook technique used throughout much of the world was likely used to catch stingrays. Almost every part of the fish was used. They were eaten as a food source, though there were taboos among the Makantol about the makers of stingray tools eating their medium; stingray skin, like sharkskin, was rough and could be used like sandpaper to smoothen out carvings, and their barbs were used in multiple tools. Stingrays also featured heavily in the cosmology of Manus. Pei, the Manus word for stingray, is a Manus constellation which closely equates to the Western constellation Scorpius. There is a myth in which a neighboring constellation representing a shark bites the tail of pei. When this is observed in the night sky, one can expect choppy seas, paralleling the struggle of a stingray fighting for its life. In general, the Manus were very talented at reading the skies. They used their knowledge of lunar cycles to take advantage of the best times to fish for different species.

|

| Alternate view of 2019.20.2 Bowers Museum Purchase |

Sting is my Name

Short stingray barb tools, similar in shape and dimensions to daggers also served a variety of other functions on the islands. Given that many of the smaller barbs on a stingray’s tail are incredibly sharp, these objects were often used as an awl of sorts for piercing holes in bundles of leaves. These punctured bundles could then be secured to the wooden frames of houses as roofing either by using wooden pegs or sewing them on. An early ethnographer claimed (likely erroneously) that stingray daggers were never used for combat, but instead served as files for detailing on woodworking projects.

Stingray spears were often used outside of combat as their multiple points excelled at catching fish. Stingray knives could be used in the preparation of sago to break up the larger blocks of sago pith and it was observed that stingray hair ornaments similar in appearance to the knives were worn by women.

|

| Various spear heads and stingray daggers from the Admiralty Islands featured in Hans Nevermann's Admiralty Islands (1934) |

Pointed Argument

Despite the object’s shape and size indicating that it is a knife, some of its elements are more characteristic of spear heads. Certainly, that the tip of the barb is broken does indicate that it was used rather forcefully at one point, and it is difficult to tell exactly what the tip would have originally looked like. As it stands now the object is more effective as a slicing tool than a piercing one, but this might not always have been the case. Most stingray daggers have either undecorated or figurative decorations on their midsection. This object has abstracted crocodilian designs, which tended to be used on spears. The butt end of this knife is also an odd shape, rounded rather than curving to a point as most do. It is less patinated in this section, which indicates that part of the object may have been removed well after it was made. While it is almost certain that this object was used as a knife, these points raise interesting questions about the history of this object.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments